When biologist Jay Savage first described the Golden Toad in 1964, hundreds of males were observed to gather for their annual breeding rituals in the ephemeral pools high on the ridge-line of the Monteverde Cloud Forest Preserve. This population was stable for more than 20 years, but declined sharply over a period of just 24 months; from the 1500 individuals observed in 1987, the population fell to a single toad seen at one of the well-known breeding pools in 1989— none have been seen for almost thirty years. The Golden Toad’s demise initiated the recognition of a global amphibian decline that continues to this day, and was the alarm bell for an extinction crisis that has continued to haunt the 21st century.

But despite a wealth of scientific investigation into the possible causes for the Golden Toad’s extinction, a steadfast consensus has yet to be reached. This is one of the questions that we intend to answer on our expedition into Monteverde this summer, but before our departure, it is worth considering the different theories for the toad’s extinction, and the evolution of scientific knowledge surrounding the global amphibian decline.

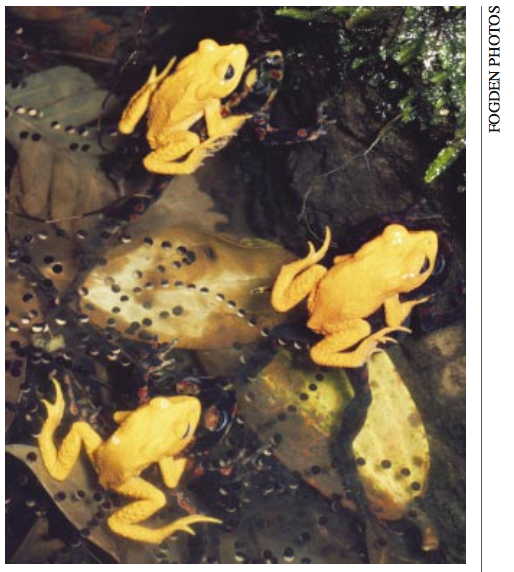

A photo of Golden Toads at their breeding pools, found in an essay by Alan Pounds.

“Underground or Extinct,” 1992

Marty Crump, and her graduate student Frank Hensley were some of the very last people to have seen the Golden Toad alive, and their paper published in Copeia in 1992 informed readers of the species’ apparent disappearance. In their consideration of the factors leading to the toad’s demise, the authors rule out the usual suspects of “habitat destruction, introduced predators, and collecting” because of the protected status of the toad’s habitat— “an area approx. 0.5 km by 8 km within the Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve at elevations between 1500 and 1620 meters” (Crump et. al, 1992). Only a few years after the initial disappearance of the species, Crump and her co-authors were not yet ready to begin to draw conclusions about the causes of the toad’s extinction; however, they did write that their available data— based on the weather patters and physical characteristics of the breeding habitat— implied that warmer-than-usual water temperatures and less rainfall during the dry season of 1987 might have led to “adverse breeding conditions” for the highly specialized species (Crump et. al, 1992). A few years later, Crump would collaborate with another graduate student and current Monteverde resident, Alan Pounds, to draw conclusions about the toad’s extinction in more detail; in 1992, however, she was still relatively hopeful, writing that “the toads may be alive and hiding in retreats awaiting appropriate weather conditions” (Crump et. at, 1992); despite her optimism, the species has not been seen since her writing.

An excerpt from Crump's 1992 paper considering the Golden Toad's demise, indicating that there were unconfirmed sightings as late as 1990.

“The Climate-Linked Epidemic Hypothesis,” 2006

In 2006, Alan Pounds— Marty Crump’s former graduate student— published a paper in Nature and, along with his thirteen co-authors, confidently pointed his finger at climate change as the enabler of the global amphibian crisis. By this time, the Golden Toad’s killer had been identified as a pathogen called chytrid— a parasitic fungus that blocks the pores of a frog’s skin, ultimately causing cardiac arrest— but the cause of the fungus’ spread was still unknown. In their 2006 paper, Pounds and his co-authors theorized that global warming not only allowed the fungus to climb into the Golden Toad’s undisturbed habitat, but also crippled the toad’s defenses against the parasite. If chytrid was the bullet that killed the Golden Toad, they reasoned, then global climate change was the gun. Their theory was termed the “climate-linked epidemic hypothesis” (Moore, 2014), and they advocated for serious attention to be directed toward climate change as a significant and “immediate threat to biodiversity” across the planet (Pounds et. al, 2006).

Pounds et. al's article implicating climate change in the extinction of the Golden Toad.

“The Spatio-Temporal Spread Hypothesis,” 2008

Unfortunately, not everyone agreed about the role of climate change in the spread of chytrid and the Golden Toad’s demise. In 2008, Karen Lips published a paper challenging the claims made by Pounds and his co-authors about the link between climate change and the spread of the amphibian-killing fungus. Lips conceded that “although climate change seriously threatens biodiversity and influences endemic host-pathogen systems,” her study “found no evidence to support the hypothesis that climate change has been driving outbreaks of amphibian chytridiomycosis” (Lips et. al, 2009). Instead, Lips advocated for the “Spatio-Temporal Spread” hypothesis, arguing that “several discrete introductions of the exotic pathogen and its subsequent wave-like spread” across land areas and through populations was not the fault of climate change, but of individual introductions and a directional spread across the continent (Moore, 2014).

Karen Lips' map showing the theorized spread of chytrid, reproduced from her paper.

“The Climate Catalyst,” 2013

Despite the debate behind its role in the spread of the chytrid fungus that wiped out the Golden Toad, climate change’s impact on threatened species has been widely recognized by the scientific community over the last decade. In 2013, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) released a study that implicated amphibians as one of the most vulnerable groups to climate change. The report stated that up to 900 amphibian species— 15% of the global population— were not only highly vulnerable to climate change, but already threatened with extinction. Despite the polarization between some scientists as to global warming’s specific role in the spread of the chytrid fungus, it seems obvious that climate change is affecting vulnerable populations of threatened species across the planet, and the Golden Toad is widely considered today to be “the first terrestrial extinction to be linked to climate change” (Moore, 2014).

The last available scientific research investigating the Golden Toad’s extinction was published close to a decade ago, but scientists still continue to investigate the global amphibian decline today. It is possible that the exact collaboration between the different causes of the toad’s demise will never be completely understood, but there is no shortage of researchers still working to find an answer to the riddle. When we return to Monteverde in June of 2018, we will talk with the scientists who still live and work in the heart of the Golden Toad’s historic habitat; it is possible that recent revelations within the last ten years might shed new light on the mystery of the Golden Toad’s demise.